By Laura Chow Reeve, Youth Engagement Manager with the Virginia Sexual & Domestic Violence Action Alliance

As advocates and preventionists, we often name safety, healing, and prevention as both our priorities and core values. We want to center these things, not only for survivors of gender-based violence but for all communities. Those conversations around what actually keeps us safe, what actually allows survivors and communities to heal and thrive, and what will actually end violence, need to address the inadequacies and harm inherent in incarceration and policing. This is a particularly necessary and urgent conversation as local and national organizers rise a call to #DefundPolice due to present and historical Anti-Black Violence committed by law enforcement.

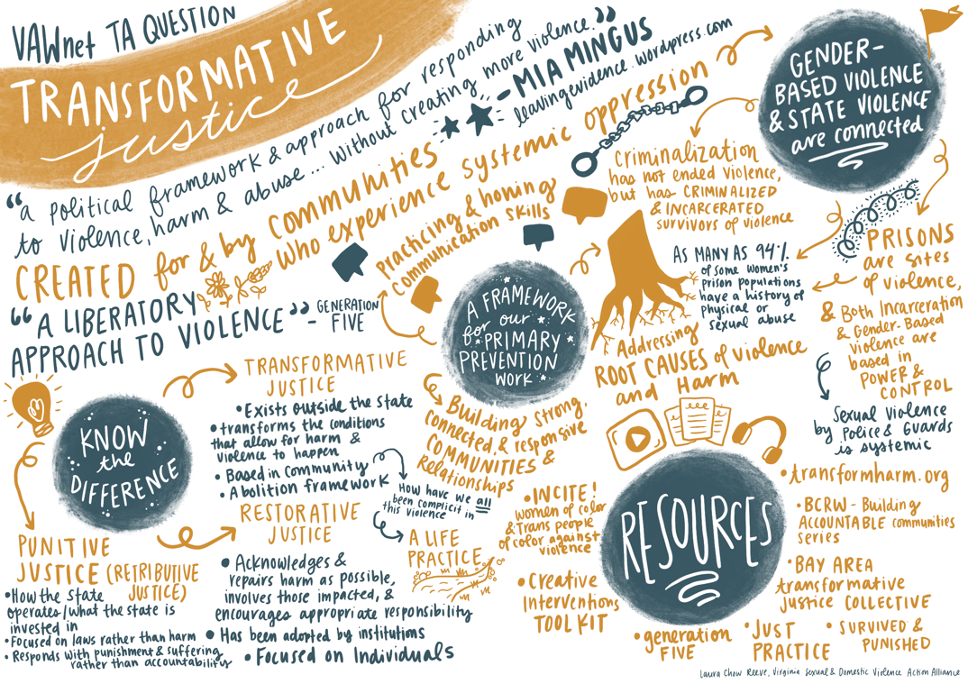

Mia Mingus, writer and organizer with the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective, describes Transformative Justice on her blog Leaving Evidence as “a political framework for responding to violence, harm & abuse…without creating more violence.” Transformative Justice was created for and by communities who experience systemic oppression, have been targeted by police and carceral systems, and who often have not had access to institutionalized responses to harm. Some of the reasons include, but are not limited to, being undocumented, previous violent or harmful interactions with police individually, in their communities, or historically, the criminalization of Black, Indigenous and People of Color, or harassment due to their gender identities as trans women, men, or gender non-conforming people.

Before I dive deeper on this topic, I’d like to name that while this may be a new conversation for the mainstream domestic violence movement, women and gender non-conforming organizers in abolitionist and anti-racist feminist spaces have been doing this work for a long time. In fact, one such organization, INCITE!, a network of radical feminists of color organizing to end state violence and violence in our homes and communities, celebrated the 20th year of its founding in April. There are a lot of resources and tools to learn from, and it is important to remember that not all work is for mainstream advocates to lead; it is important rather to support, uplift, and provide resources to work that is rooted in and has been developed for and by a specific community.

Understanding the Difference: Punitive, Restorative, and Transformative Justice

We have been socialized to believe that punishment is justice. Punitive Justice focuses on laws rather than harm, and responds to laws being broken with suffering, isolation, and removal from community. Culturally, we also use punishment in our everyday interactions with our children, our families, and our friends often responding to hurt, harm, or “breaking rules” through similar mechanisms. Our response is often to take away resources and care in response to harm, rather than working together to understand and address why that harm happened in the first place.

“It’s not punishment that gets us to safety. It’s accountability.” – Danielle Sered, Common Justice

While Restorative Justice (RJ) and Transformative Justice (TJ) are often thrown around as synonyms, part of my learning started at understanding the key differences between them. While both RJ and TJ look to address harm outside of punitive measures, TJ is an abolitionist framework and approach that sees how our justice system was built on and replicates violence and oppression.

Restorative Justice, defined by Howard Zehr of the Zher Institute for Restorative Justice, “is a process to involve, to the extent possible, those who have a stake in a specific offense and to collectively identify and address harms, needs and obligations, in order to heal and put things as right as possible.” In the United States, RJ, as we have come to know it, “emerged in the 1970s as an effort to correct some of the weaknesses of the western legal system while building on its strengths.”However, it is also important to name that many RJ practices, such as talking circles, have been adopted from Indigenous practices around the world.

On an episode of the Justice in America podcast, Mariame Kaba, the founder and director of Project NIA, also highlights how RJ focuses on individual interventions, while TJ thinks about how our larger systems need to be transformed—“RJ, because of its focus on the individual, the intervention is on individuals, not the system. And what transformative justice, you know, people, advocates and people who have kind of begun to be practitioners in that have said is we have to also transform the conditions that make this thing possible.”

And, as Mimi Kim, co-founder of INCITE! and Creative Interventions Toolkit, named so clearly in the Abolition Feminism Celebrating 20 Years of INCITE! virtual event, “There is no transformative justice that involves law enforcement. Period.” However, RJ has been utilized in and adopted by systems that involve law enforcement and larger justice systems.

While different, both RJ and TJ practitioners and advocates have named the distinct differences between punishment and accountability. Common Justice, an organization that develops and advances solutions to violence that transform the lives of those harmed and foster racial equity without relying on incarceration, reminds us that while punishment is done to people, accountability is done with people. Punishment does not require any active engagement, but accountability “requires five key elements: (1) acknowledging one’s responsibility for one’s actions, (2) acknowledging the impact of one’s actions on others, (3) expressing genuine remorse, (4) taking actions to repair the harm to the degree possible, and (5) no longer committing similar harm.”

Gender-Based Violence and State Violence are Connected

Survived and Punished, a national collective of organizations in New York, Chicago, and California who have launched campaigns demanding the mass commutations of survivors, compiled data that shows how prisons institutionalize sexual and domestic violence. For example, as many as 94% of some women’s prison populations have a history of physical or sexual abuse before being incarcerated and that there were over 3,200 transgender people in US prisons in 2011-12 and nearly 40% reported sexual assault or abuse that occurred in 2012 by either another prisoner or staff.

Incarceration and collaboration with law enforcement has not ended gender-based violence. Rather, survivors have been criminalized and incarcerated as a result of experiencing gender-based violence and many continue to experience violence while they are incarcerated. When having conversations about what makes survivors safe, we cannot create a binary that assumes perpetrators are incarcerated and survivors are not. Furthermore, we have to reckon with the knowledge that all incarcerated people experience both interpersonal and systemic harm, and that prisons do not have a place in a world truly free from violence.

A Framework for Primary Prevention

“If we really want to be a nation where violence is uncommon, we will have to eliminate the racial inequities that exist in things like schooling, income, access to health care and mental health care, and in all of the fundamental social services that will make or break the wellbeing of a community. We have to stop pretending that violence is a problem that we cannot solve." – Danielle Sered, Common Justice

In the Barnard Center for Research on Women’s video “What is Transformative Justice?,” Shira Hassan, community activist and facilitator with Just Practice, says “I want people to take the values into schools, or I want people to take the values into broader institutional work. And those values are around ending prisons and around transforming our understanding of accountability and disconnecting the idea of punishment and justice.”

So, for those of us in the sexual and domestic violence field who are excited by TJ and its approach, the question of where our sexual violence and domestic violence agencies, coalitions, and organizations fit in this work is important to address—especially when our work is largely funded by state and federal systems. This, of course, is a larger question and conversation that we need to hold and address within our organizations about the professionalization of our field and our reliance on the criminal justice system in response to harm through our service provision.

There is possibility in bringing the values of TJ into our work. One of the places that I think those values already have connection and alignment is in our primary prevention work. Primary prevention, like TJ, addresses the root causes of violence and transforms our communities and larger culture so that violence is no longer possible. In the same video from the Barnard Center for Research on Women, Mia Mingus says that TJ “also, most importantly, helps to create and cultivate the very things we know help to prevent violence. Things like resilience, safety, healing, connection, all of those things.”

Our primary prevention work should strive towards transforming our relationships, communities, and larger society so that violence is no longer possible. If we are truly to take TJ’s values and framework into our primary prevention work that must include meaningful conversations around what truly makes our relationships and communities healthy and equitable.

Further Reading and Resources:

- Transform Harm is a resource hub about ending violence. It offers an introduction to transformative justice. Created by Mariame Kaba and designed by Lu Design Studio, the site includes selected articles, audio-visual resources, curricula, and more. Topics include Transformative Justice, Restorative Justice, Community Accountability, Carceral Feminism, and Healing Justice.

- INCITE!-Critical Resistance Statement is a statement on Gender Violence and the Prison Industrial Complex released in 2001 by a network of radical feminists of color organizing to end state violence and violence in our homes and communities. The statement calls social justice movements to develop strategies and analysis that address both state AND interpersonal violence, particularly violence against women.

- “My Transformative Justice Workbook” is a resource created by the Virginia Anti-Violence Project and the Virginia Sexual and Domestic Violence Action Alliance after 6+ months of conversations and a desire to engage our communities around Transformative Justice and how we both respond to and prevent violence outside of state-based systems that target and criminalize people of color ( particularly black people and communities), queer and trans people, poor folks, immigrants and undocumented communities, disabled folks, and other marginalized communities.

- generationFIVE is unique amongst national anti-violence organizations in recognizing that our goal of ending child sexual abuse cannot be realized while other systems of oppression are allowed to continue.

- Four Guiding Principles for Making our Cities Safer from Common Justice is a video by Common Justice describing the Four Guiding Principles necessary for addressing violence. Common Justice develops and advances solutions to violence that transform the lives of those harmed and foster racial equity without relying on incarceration.

- How to Survive the End of the World: The Practices We Need: #metoo and Transformative Justice Part 2. How do we learn from apocalypse? How do we move through endings with grace, rigor, and curiosity? In this podcast, the Brown sisters (Autumn Brown and Adrienne Maree Brown) talk with transformative justice practitioner Mariame Kaba about the practices that we need as a community to move through endings, address harm and grow beyond it.

- We Choose All of Us encourages practices of self-reflection and storytelling to plant and nurture the seed that reconnects us to us. Through visual art, poetry, and storytelling, We Choose All of Us promotes a new way of being, with relationships based on mutuality, an abundance and sharing of resources, and organizing across social justice issues with impacted communities at the center.

- PreventIPV.org offers a wealth of information to assist individuals and communities in building their capacity to engage in prevention work as it relates to gender-based violence. Included is a collection of resources such as training tools, campaigns, promising programs, evidence, policies, and other materials that can be adapted to advance your prevention efforts.

- What Does Gender-Based Violence Prevention Look Like in the Face of COVID-19? At this time we are seeing the work that must be done to promote 1) health equity, 2) racial justice, and 3) community care as sustainable remedies to foster healthy and thriving communities. This page includes various resources capturing diverse perspectives on this work as it relates to the COVID-19 crisis.