by Patty Branco, NRCDV Senior Technical Assistance and Resource Specialist

One of my favorite things about working as a Technical Assistance Specialist for the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence is the opportunity to research and respond to inquiries about innovative or alternative approaches to serving survivors of gender-based violence in more holistic and engaging ways. For many, the summer season inspires increased interest and opportunity to deepen their spiritual relationship with nature and connect with the earth as a way to foster healthy families and communities. Additionally, the physical, psychological, and social benefits of outdoor activity are well documented as a strategy for enhancing overall well-being.

Therapeutic horticulture refers to interventions using nature or plant-related activities, such as gardening and farming, to improve participants’ physical, psychological and social wellbeing (Renzetti, Follingstad & Fleet, 2014). Therapeutic horticulture can be implemented in a broad range of settings, including domestic violence shelters, often as an adjunct to core services and programming. This post highlights the benefits of establishing voluntary garden and farm programs for shelter/safe house staff, residents, and domestic violence agencies.

Promoting psychological and social wellbeing

Working in gardens or on farms can be an avenue for survivors and their children to heal and cope with trauma, with a potential impact on the wellbeing of the entire shelter. Available studies within diverse settings indicate that therapeutic horticulture programs are effective for reducing stress, depression, and negative feelings, as well as in promoting relaxation, social inclusion, and self-confidence (Renzetti, Follingstad & Fleet, 2014).

For advocates and residents alike, a garden in the shelter can help with promoting self-care. For example, staff and volunteers can use the garden as a place to relax and enjoy their lunch breaks. Parents and children residing in the shelter can spend fun, quality time working together in the garden. Activities like planting, weeding and watering can be therapeutic and recreational for children who have endured trauma. Horticulture programs can also serve as a childcare function, creating activities for children while parents attend counseling or search for jobs and affordable housing.

Additionally, survivors who are immigrants/refugees or from rural areas, who gardened or farmed in their communities or home countries or during childhood, may welcome the opportunity to work the land while in shelter as a way to reconnect with their family and cultural backgrounds: “I always wanted to garden but didn’t have the space. At my grandparents in Mexico, I watched them garden corn, wheat, squash, beans, sugar cane, lemon, pomegranate, flowers and herbs” (Survivor, Project GROW).

“I feel the gardening program has made my children become more gentle with plants and flowers, also they have learned all things grow with care and love.” ~ Survivor, Project GROW

Developing skills and promoting economic empowerment

Experiencing domestic violence often undermines survivors’ ability to find or maintain employment and further their skills and education. Increasingly, advocates and researchers are focusing attention on developing and promoting programs that economically empower survivors. In addition to its therapeutic benefits, horticulture in shelter can help survivors on their path to economic independence. By working in gardens and on farms, staff, volunteers, survivors and their children can learn and/or apply valuable marketable skills and gain work experience.

This video describes the implementation of a farm program at GreenHouse17 – the primary provider of services to victims of domestic violence in Central Kentucky. At GreenHouse17, residents are offered voluntary opportunities to participate in farming activities in exchange for a small stipend as compensation. For residents who do not wish to participate directly in farming, opportunities are available to engage in farm-related activities such as cooking farm-to-table meals, making flower arrangements, as well as crafts and body products from harvested products, which can be sold at local farmers’ markets, or ordered for special events such as weddings. (For more inspiration, see also Thistle Farms’ model of offering hope and healing to trauma survivors via employment in various social enterprises.)

“Some people come through with no work history. Some people, you know, whatever reason, it gives them – and it’s a small stipend – but then it gives them that work experience, a good work referral, a small check to kind of get things started. And so on many levels it’s an amazing thing because it’s therapeutic, it’s employment, and you get treated like an employee.” ~ Shelter Staff at GreenHouse17

Revitalizing shelter spaces and connecting to the community at large

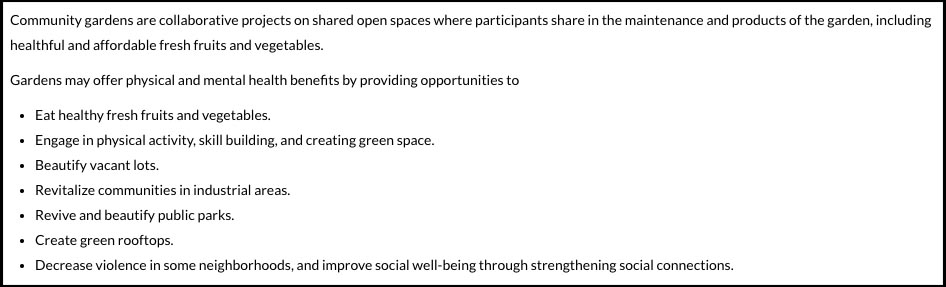

Ultimately, therapeutic horticulture programs benefit not only individual survivors and advocates but the shelter and community at large. Gardens can beautify and enliven the shelter space, creating a homier atmosphere where residents can feel more welcome and comfortable. Besides, as shelters turn brown desolate areas into lush gardens, they have the potential of beautifying and revitalizing their local communities, especially in urban and industrial areas.

It is worth noting that the creation of green spaces, such as turning vacant parking lots into community gardens, can help promote overall health, beautify and revive communities, decrease violence in some neighborhoods, and improve social well-being through strengthening social connections. More information on how greening communities can promote health and reduce violence can be accessed from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Recreation and Park Association, and the National Environmental Education Foundation.

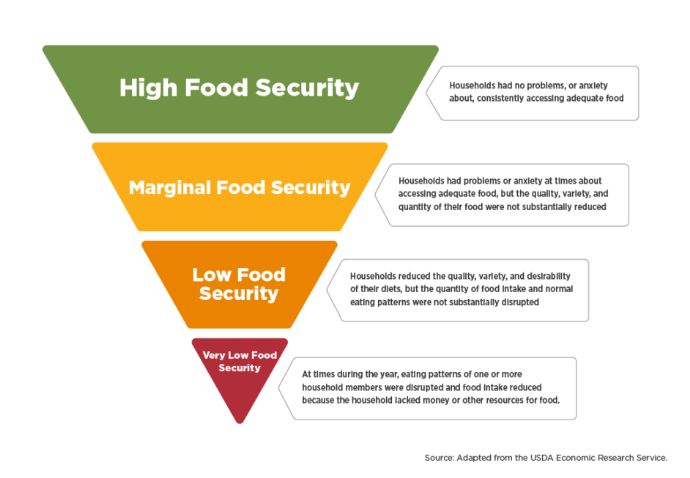

Addressing food insecurity

We know that shelter residents (and often staff, for that matter) – especially individuals from traditionally marginalized communities – are likely to experience food insecurity due to a variety of factors that may include poverty, abuser control of family resources, and disrupted mealtimes. Shelter advocates help meet the food-related needs of survivors and their children by connecting families with critical economic security programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP – formerly known as food stamps) (see The Difference Between Surviving and Not Surviving: Public Benefits Programs and Domestic and Sexual Violence Victims' Economic Security). In addition, due to scarce resources and limited food budgets, shelters often rely heavily on canned and processed foods obtained via community donations and wholesale stores to feed their staff and residents. One shelter staff explains, “because we’re a poor nonprofit, what happens is we feed everybody chicken nuggets and French fries, because that’s what we can afford, processed food everywhere” (Renzetti, Follingstad & Fleet, 2014, p. 16).

While most shelters do not have food gardens, a few domestic violence programs across the country have learned the benefits of growing a vegetable and fruit garden to supplement the food supply at the shelter and to provide a healthier and more nutritious diet to advocates, survivors and their children. For example, through a two-year pilot project known as Project GROW, nine domestic violence shelters across California established edible and decorative gardens and other food and nutrition programs. This pilot project has shown that shelter gardens can help address the need for increased food security in domestic violence agencies. Produce harvested by staff and residents can be used to cook fresher and more nutritious meals at the shelter, and can also be used as barter at local farmers’ markets to obtain additional produce.

Keep in mind that, especially in shelters serving large immigrant and culturally-diverse populations, thoughtfulness about planting fruit, herbs and vegetables that are familiar to survivors and their children can be instrumental in supporting the shelter’s efforts towards inclusiveness and the creation of more welcoming environments.

“We like to get the fresh vegetables, otherwise, we have to eat frozen since these are the only fresh vegetables that the shelter gets.” ~ Survivor, Project GROW

Conclusion

Of course, there are hurdles to overcome as domestic violence shelters explore the development and implementation of therapeutic horticulture programing. Available evaluation reports on GreenHouse17 and Project GROW discuss some of the main challenges (e.g., lack of funding, overworked staff, shortage of space, toxic soil, etc.) that may face shelters implementing and maintaining farm and garden programs. A key strategy for addressing some of these challenges includes forging new alliances between victim advocates and non-traditional partners such as community gardeners, farmers’ markets, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) projects, nutrition educators, among others. However, as we walk through lessons learned from Project GROW and GreenHouse17, as well as the powerful testimonies of survivors and advocates, we can’t help but see a promising picture – one in which therapeutic horticulture is a worthy investment for improving the lives of both advocates and residents at domestic violence shelters.

“The garden gives me air. I breathe fresh air. It relaxes me. I return to life. I stop now and notice the flowers.” ~ Survivor, Project GROW

(

(