One of the largest investigations ever conducted on childhood trauma is the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, which explores the long-term health and well-being of adults who experienced trauma in childhood. ACEs include direct verbal, physical, or sexual abuse, as well as what is termed “family dysfunction” – such as having family members who are/have been incarcerated, mentally ill, or substance abusing, families who are/have experienced domestic violence, or absence of a parent because of divorce or separation. Recent data assessing ACEs in adults from five states revealed that well over half (59.4%) reported at least one ACE and 8.7% reported five or more ACEs (MMWR, 2010).

One of the largest investigations ever conducted on childhood trauma is the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, which explores the long-term health and well-being of adults who experienced trauma in childhood. ACEs include direct verbal, physical, or sexual abuse, as well as what is termed “family dysfunction” – such as having family members who are/have been incarcerated, mentally ill, or substance abusing, families who are/have experienced domestic violence, or absence of a parent because of divorce or separation. Recent data assessing ACEs in adults from five states revealed that well over half (59.4%) reported at least one ACE and 8.7% reported five or more ACEs (MMWR, 2010).

While we may wish to protect the children in our lives from any exposure to harm, the truth is that most children in the U.S. are exposed to violence in their daily lives (either directly or indirectly). According to the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV), over half (60.6%) were exposed in the past year, and more over their lifetimes – with lifetime exposure rates at 1/3 to 1/2 higher than past year exposure (OJJDP, 2009).

When it comes to exposure to domestic violence in childhood, defined as living in a home where an adult employs tactics of abuse in a pattern of coercion and control against an intimate partner, about 20 million children under 18 will have had this experience during the course of their young lives – 6.2% in the past year and 16.3% since birth (US Census Bureau, 2011; Finklehor, Turner, Hamby, & Ormrod, 2011; Finklehor, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, 2008). Rates of child sexual abuse are estimated at nearly 1 in 10 (9.8%) over a lifetime and 6.1% in the past year (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, Hamby & Kracke, 2009). We also know that children who experience one type of violence are more likely to experience other types of violence (Finklehor, Turner, Hamby, & Ormrod, 2011). The impact of childhood exposure to violence depends on a number of risk and protective factors and variations in the nature and severity of abuse, the presence and degree of other family stressors, a child’s own coping skills, among other unique aspects of a child’s experience (Edleson, 2006). Childhood trauma can be quite complex – while this collection’s particular focus is through a gender based violence lens, you can learn more about other experiences of childhood trauma through the National Child Traumatic Stress Network and/or the Child Welfare Information Gateway.

Experiences of trauma may not be limited to an individual’s lifespan. It is important to understand other types of trauma which include:

- Historical Trauma: Cumulative trauma existing over a lifespan and across generations, historical trauma considers significant group experiences in history such as slavery, genocide, and forced acculturation.

- Intergenerational Trauma: Transferred from one generation to the second and further generations, intergenerational trauma may also be referred to as the transgenerational cycle of violence.

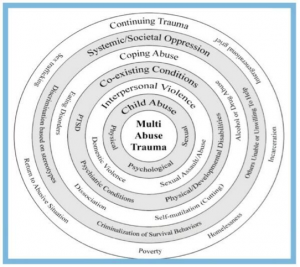

- Multi-Abuse Trauma: This term describes the experience of navigating multiple layers of trauma/oppression and/or co-occurring issues that negatively impact safety, health, or well being.

- Compound/Complex Trauma: Describes prolonged and repeated abuse involving repetitive or prolonged stressors over time.

The National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma, and Mental Health provides this visual for understanding the layers of trauma a person may experience in their lifetime and how the co-existing conditions, coping strategies, and systemic oppression can add to a person’s cumulative trauma (Edmund & Bland, 2011).

The National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma, and Mental Health provides this visual for understanding the layers of trauma a person may experience in their lifetime and how the co-existing conditions, coping strategies, and systemic oppression can add to a person’s cumulative trauma (Edmund & Bland, 2011).

As Joan Schladale of Resources for Resolving Violence notes, “Trauma is a common human experience that is largely overlooked in existing explanations of and responses to human behavior.” Once we understand trauma in this way, we can truly begin to embrace trauma-informed approaches as critical to our work. Trauma-informed practices incorporate an understanding of the role that trauma plays in our lives and recognizes behaviors and reactions to trauma as adaptations or survival techniques. They explore the ways in which trauma has shaped a child’s feelings and reactions, core beliefs, sense of stability, choices, and understanding of how to navigate the world.

When our approaches for working with children are trauma-informed, they become prevention strategies – focused on creating environments where children can thrive, providing them with the tools necessary to navigate their lives in safe and healthy ways, and building their confidence in and appreciation for the assets and strengths they possess.