By Rev. Miller Hoffman, Metropolitan Community Churches

Transgender women of color interrupted the flow of the first-ever presidential CNN-sponsored LGBTQ town hall October 10 after Ashlee Marie Preston’s invitation to ask a trans-related question at the forum was withdrawn by organizers. Whatever the reasoning, the rescindment of Preston’s active participation was experienced by many people within trans communities as a silencing. Though still invited to attend, Preston and others decided not to be present so that they would not imply support or be tokenized by efforts to “diversify” the event. Some participants who did attend chanted “Trans Lives Matter,” and others used the microphone to strategically redirect the discussion and to name the violent targeting of trans folks, as well as their simultaneous erasure from the discussion.

What happened at the CNN-sponsored town hall mirrors what we know to be true of intimate partner violence and rape culture: survivors and victims are often dismissed as emotional and unreliable and erased from official conversations about the violence we’ve experienced. The trans women who were forced to command the candidates’ attention are expanding the legacy of survivors of domestic and sexual violence, as well as the legacy of trans activism and protest, including the Cooper Do-nuts, the Compton Cafeteria, and the Stonewall riots. Each of these watershed moments of revolution featured police targeting of early trans women and men, crossdressers, effeminate gay men, stone butches, scare queens, and others, many of whom were people of color and people made vulnerable by poverty, homelessness, and unemployment.

Although some progress had been made for trans and genderqueer rights in the 21st century, since 2017 most of the few protections and legislative inroads have been curtailed or eliminated. These cuts and reversals have done harm to trans and genderqueer access to and participation in education, health care, disease prevention, housing and homelessness services, adoption and foster care, prisons, military service, asylum, and protection under Title VII and Title IX (National Center for Transgender Equality). Already struggling with stereotypes and mischaracterization in public restrooms and on public transportation, people within the transgender and genderqueer communities are again under legislative siege across the full spectrum of public and private life.

Official legal attacks and policy rollbacks contribute to a social climate that devalues trans and genderqueer people. The way that officials, administrators, and elected representatives talk about trans-related issues – let alone transgender bodies and genderqueer lives – affects the national discourse about us. When authority figures attack us with policy and language, they encourage and reproduce violence against us at local and personal levels. We know that people who are demeaned and disbelieved are particularly vulnerable to domestic and sexual violence. We know that people wielding power and control against intimate partners are aided by sexism, heterosexism, racism, transphobia, and other forms of systemic oppression.

Even seemingly frivolous behavior is significant to this culture of violence against trans and genderqueer folks. At the LGBTQ town hall mentioned earlier, Sen. Kamala Harris began her initial remarks by providing the pronouns she uses, “My pronouns are she, her, and hers,” and the CNN news anchor Chris Cuomo responded glibly, “Mine, too.” Cuomo later apologized, and he did well to do so. Regardless of his intentions, by mocking Harris’s efforts to call attention to the importance of asking for and providing pronouns across gender identity, he encourages others to dismiss this small but important way to show respect for trans and genderqueer people.

Supporting Trans and Genderqueer Communities

Since our communities started counting, the numbers of transgender people murdered has been climbing globally. The Remembering Our Dead project (trigger warning) began with 14 names and two countries in 1999; as of September of this year, more than three hundred names have been compiled from 13 countries. This number is almost certainly low. We have been killed in every imaginable way; we are beaten, stabbed, hanged, strangled, hit by cars, drowned, shot, raped, and thrown from bridges. Most of those killed are women, mostly women of color. The global numbers show a horrifying concentration of violent trans deaths in South America, particularly Brazil, as well as the United States and India. Overwhelmingly the transgender people murdered in the United States have been black. And many of those killed were murdered by boyfriends and lovers. In 2018, Zella Ziona was murdered in Maryland because she saw her boyfriend in the neighborhood and flirted playfully with him in front of his friends. Itali Marlowe, who is the 20th trans person to be counted among those murdered in the U.S. this year, was shot to death by the man she lived with.

In November 1998, Rita Hester was murdered in her home in Boston. The Remembering Our Dead project was created directly in response to her murder, which like many violent crimes against trans people was unsolved. A candlelight vigil was held the following November in San Francisco, and these were the beginnings of what became the annual Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDOR) held on November 20. Last year events took place in more than twenty-nine countries. Holding a TDOR event is a strong show of support for the trans and genderqueer communities. If you are thinking about organizing one in your area, there are a number of important considerations before finalizing your plans.

Start planning early.

It is very important to include people in your planning who are among the groups most directly impacted. In the case of a TDOR event, this certainly means transgender and genderqueer people and, importantly, trans women and trans women of color. Building collaborations with transgender and genderqueer organizations and reaching out to ask how allies can support their efforts is a good place to start. Allies understandably sometimes want to own our responsibility for ending anti-trans violence and remove the burden from trans shoulders, but it is important to take direction from the folks we want to help.

Because not all trans or genderqueer folks will have an interest or the energy to participate in planning, allies should begin asking early for community members to join the planning conversation. There is an important difference between having trans folk and trans women of color contribute substantively to the event, as opposed to inviting trans people to attend or speak at an event after the meaningful decisions have been made.

Choose a venue.

Often, the most available community spaces for queer and trans events are congregational buildings or bars. While these are significant positive presences in our history, as well as our current queer and genderqueer lives and communities, they also can be sites of discomfort and even pain for many trans and genderqueer people. Start early to secure a space that can be most neutral and emotionally safe for the most people. Be mindful of the physical accessibility of the venue.

Invite speakers, advocates, and other human assets.

When choosing speakers, take care to include the voices of those most directly impacted by anti-trans violence, while also including as much of an array of trans and genderqueer diversity as possible. Beginning early will help to make this possible. Police chiefs, mayors, and politicians often are eager to speak at our TDORs and other events; know that it is okay (and perhaps preferable) for these authorities to attend and silently support us. If it seems important to include these voices, consider how (and whether) they have demonstrated concrete support throughout the year through policy and practice. Take care not to simply defer to their role or rank. How are they showing support and interest in our safety? How are they framing and responding to violence against us?

When considering security, think carefully about whether to invite a police force. Some police are trans and genderqueer, of course. There is, though, a painful and complex history of tension and violence by the police against LGBQ communities, T and nonbinary communities, communities of color, immigrant communities, other marginalized and oppressed communities, and the people who live at the intersections of these groups. For these reasons, events like the annual New York City Dyke March train and prepare their own community volunteers to serve as security, marshals, and negotiators. Discuss what options are available for you and, if in the end a police presence is planned, offer training to the officers to communicate the community’s needs and expectations during the event.

Because the event is highlighting parts of our communal trauma experiences, many TDOR planners have taken steps to invite social workers, counselors, or therapists to be available for emotional support. These counselors are given a station in the main area or a “comfort” room is set aside near the main program for participants to access confidentially and voluntarily. It is critical that these professionals are well-trained in pronouns and other matters of trans experience, racial justice, and other relevant justice matters.

Create event content.

From beginning to end, think about how the event can practice and model what we expect and want from a world that respects and celebrates trans and genderqueer people.

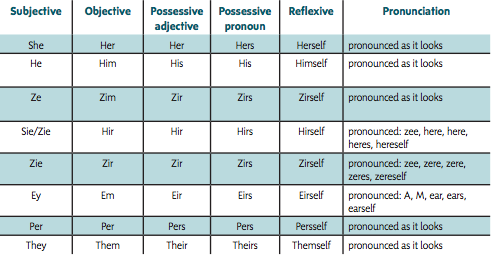

- Make opportunities to ask for and provide pronouns during every part of the event, with appropriate ways for folks to opt out. (Transgender and genderqueer people will decline to provide pronouns sometimes because we don’t feel safe, we don’t necessarily have a single pronoun or any that fit, or for other reasons.) For example, you might invite speakers to include their pronouns at the beginning of their remarks, provide pronoun nametags, and include pronouns as you greet people at the door. (“Hello, thanks for coming! I’m Miller and use he/him or they. People are gathering just ahead and to your left…”) See Gender Identity Basics and Terminology for more information.

- In addition to including the impacted communities in planning and decision-making, it’s important that TDOR events highlight the disproportionate weight of violence against transgender women of color. This can be done with speakers and facilitators, with a dedicated part of the event focusing on trans women of color, through a slide show or video, or in other ways.

- It is also very important to recognize and talk about the full range of trans and genderqueer identity and experience, including trans folk on and off the binary, agender people, the many fluid gender identities, and others. This may be communicated with language throughout the program, with invited speakers, and in other ways.

- Consider reading the names of those who have been killed globally. This honors us across national and political boundaries, highlights our murders as a global epidemic, and underlines the number of our dead who are of color. There are hundreds of names, and organizers often are concerned about the time needed to read all the names. Consider, though, that the event is organized around a day of remembrance and honoring the dead. There is time. Make time.

-

Names can be read during a candle-lighting portion of the event in the middle or at the end. Some organizers make a candle-lit walk part of their event, with a reading of the names happening at a point on the path, sometimes near a cairn or other memorialized symbol for the dead. Take care for the emotional weight of reading the names, and try to have a number of readers.

Many, many names on the global list are people from Spanish-speaking countries. Not all of our communities will have people who speak Spanish fluently. Take some time to speak with your readers, and encourage non-Spanish-speaking readers to say the names with confidence rather than tentatively and with question marks in their tone.

Many names on the global list are anonymous or “Name Unknown.” Read the name and honor each of the unknown persons represented by this marker. Recognize that each entry represents a person who lived, loved, and was murdered. Recognize that, even with those entries where names are provided, we do not fully know the person.

Understand that traumatized people and people under attack may be emotional and even angry. Anger and distress are very appropriate responses to the violences directed at trans and genderqueer folks, people of color, immigrants, and those living at the intersections of these communities. Be aware that social etiquette and expectations are culture-specific, and that much of what is considered “polite” or “appropriate” is defined by hegemonic Whiteness. Create a space where fear and anger can be expressed and validated.

Understand that traumatized people and people under attack may be emotional and even angry. Anger and distress are very appropriate responses to the violences directed at trans and genderqueer folks, people of color, immigrants, and those living at the intersections of these communities. Be aware that social etiquette and expectations are culture-specific, and that much of what is considered “polite” or “appropriate” is defined by hegemonic Whiteness. Create a space where fear and anger can be expressed and validated.- Be mindful of the impulse of allies to “keep it positive” and “focus on uplifting.” There is room to celebrate progress – this can even be an important piece of a TDOR event – but, as with fear and anger, expressing grief and naming our dead is appropriate and often needed.

Organize all year.

Learning to be an ally to trans and genderqueer communities is an ongoing process. Some efforts involve relatively simple and easy steps, while others require more time, energy, and commitment. Resources are available to offer guidance on how to be a good ally and help make the world a safer and more inclusive place for trans and genderqueer communities. See, for instance, Supporting the Transgender People in Your Life: A Guide to Being a Good Ally by the National Center for Transgender Equality.

It is important to make pro-trans activism and education part of your community’s work year-round. Take care not to limit or tokenize your support to a single event or month.

For more information:

Trans Murder Monitoring Project/Transgender Europe (TGEU)

Transgender Day of Remembrance

National Center for Transgender Equality

Serving Trans and Non-Binary Survivors of Domestic and Sexual Violence