By Colleen Yeakle, Coordinator of Prevention Initiatives with the Indiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence (ICADV)

As the Indiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence (ICADV) approached its 40-year anniversary, this question felt like an urgent one. So much had changed in our communities since domestic violence program models were developed. Though we were applying new learnings along the way, these minor modifications left the assumptions and structures of our service delivery models largely unchanged.

We were not alone in this observation. In 2014, we joined with other state domestic and sexual violence coalitions and national partners in exploratory conversations about the nature and future of our work. We discussed the intersections between our work and other movements focused on eliminating oppression.

“Intersectionality simply came from the idea that if you’re standing in the path of multiple forms of exclusion, you are likely to get hit by both.” – Kimberlé Crenshaw

Most deeply, we thought about the world that we wanted to work towards—a world characterized by liberation where all of us can safely live and thrive. We thought strategically about who we needed to be, and what we needed to work on in order to pursue that vision.

Based on these conversations, ICADV initiated a parallel process with our stakeholders to assess our work. Together, we launched a multi-year process designed to re-center Indiana’s domestic violence programs and services in survivor-defined success.

Critical Reflection

As we reflected on our legacy, we felt appreciation for the services, supports and compassion that advocates worked to build for survivors over the past four decades. Prior to the 1980s, most victims of violence were isolated in their experiences without access to hotlines, service programs, institutional accountability options, or even community understanding about the dynamics of domestic abuse. We deeply valued the work, undertaken with diligence and passion to increase safety, connections and options for survivors of violence.

But we also felt dissatisfaction with the cracks in the systems that we created. The systems that we’ve built to be responsive to crisis are grounded in a sense of urgency that left us little space for meaningful reflection. We recognized that our energy was consumed by the daily work of defending and fortifying solutions that were defined over a generation ago. These solutions were built on an oversimplified idea of who a “victim” of domestic violence is, and a progression of “right” survivor decisions began with ending the relationship and typically involved engagement with the criminal and/or civil legal systems.

We recognized that the institutional response systems that have endured were mostly created by white feminists, relied heavily on law enforcement responses, and that available funding streams maintain the dominance of this mainstream response. Most critically, we recognized that many survivors were left behind because the solutions that we were working to sustain were not realistic, available, relevant, accessible or helpful for their lives.

We were conscious that we hadn’t made significant progress on our broader vision of a just world, free from domestic and sexual violence. Though most of our visions centered on creating equitable communities free from violence, with limited resources, most of our work was focused on helping people to navigate the inequities in their lives while trying to safely manage their experiences of violence. Our status quo felt insufficient, but also, fragile; and we were working in overdrive, mostly from muscle memory, to maintain it.

With this reckoning, we concluded that it was time to pause and listen to survivors. Based on the wisdom of their experiences, we decided we would adopt new strategies, services, systems and supports. We needed to know what types of services were most valued, what needs were unmet, and fundamentally, how communities could reduce violence by increasing safety and supports for all of us.

The cohort of member programs carefully defined the sample of survivors that we needed to hear from in order to ensure the inclusion of survivors with diverse identities. Particular attention was paid to hearing from survivors who have been unserved or underserved because of barriers related to identity-based discrimination, disabilities, homeless status, criminal justice histories, immigration status, or challenges related to mental health or addictions. We were committed to hearing both from individuals who had used services from domestic violence programs and from those who had not. We needed all of these perspectives to get a broad overview of what we are doing well, what other services we should be offering, and strategies that we could use to increase the awareness, availability, and competence of our services for survivors who had not known, or had reason to believe that we were there for them.

Active listening

Twelve member domestic violence programs serving communities across Indiana joined the Coalition in the process of assessment and development. We worked together for several months to determine what we wanted to ask survivors—we wanted to know about their priorities for safety, who they reached out to for support, what they felt they needed to hide, the services that were most valued, and how they thought communities should hold people accountable for their use of violence. The full interview guide is available here.

As a group, we committed to practices that would keep us accountable to survivors throughout our process including providing quarterly project updates, a copy of the final report and information about opportunities for advocacy on report recommendations. Interview participants were compensated for their time and expertise with a $25 gift card.

In the ten-month period from December 2017 through October 2018, members of the cohort conducted 91 individual interviews and five focus group discussions with survivors. Multiple methods were used to recruit an inclusive sample of participants including announcements across programs’ communication platforms, outreach to community partners (with particular attention to programs that serve communities that are marginalized), invitations on Facebook groups, word of mouth among homeless service organizations, invitations to disability service organizations, and pull-tab announcements on community bulletin boards. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish; they were conducted in the community and also with survivors who were incarcerated.

Some identities and experiences reported by the survivors we interviewed included:

- Survivors who identified as racial and ethnic minorities (12%)

- Survivors who identified as LGBTQ (11%)

- Survivors with current or previous experiences of incarceration (26%)

- Survivors working with homeless programs (21%)

- Survivors with disabilities including intellectual or developmental disabilities (23%)

- Survivors who identified as immigrants (16%)

- Survivors managing mental health and addictions (49%)

- Over half of respondents had not used a domestic violence program

What we learned

We learned that for survivors, safety required both the absence of abuse and the presence of basic needs. They told us that shelter programs could help them in separating from an abusive relationship, but absent the opportunity to earn a living wage, and to secure stable basics like safe, affordable housing and food, their choices would be limited to returning to a shelter, returning to an unsafe relationship or homelessness.

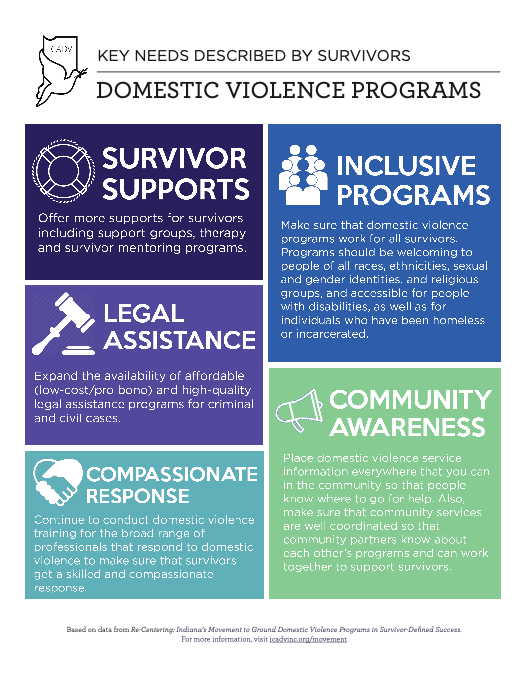

Accordingly, the recommendations from the report describe survivors’ needs for safety and support both from service providers, and more broadly within their communities. The full report and infographics summarizing recommendations are available here.

Highlights of report recommendations include:

1. Housing, housing, housing, housing.

Housing was the primary need that survivors identified in the context of safety. In defining stable housing, survivors told us that they needed housing that was both safe and affordable.

“Having a place to live. It's very difficult to find a place to rent if you have kids. And then you have to have money up front. You have to have a deposit, you have to have the first month's rent. Well, if I just left, I don't have any money. That was a big thing that I feel like that would be one reason I would ended [sic] up staying because I didn't have somewhere.”

2. Promote economic opportunity and stability.

Survivors told us that economic stability reduces their vulnerability to abusive relationships, and that it is essential for enabling them to rebuild stable lives for themselves and their children subsequent to an experience of abuse. Survivors described the need for livable wages, affordable housing, and for social safety net programs to support them through periods of crisis. They urged us to expand eligibility to social safety net protections—including expanding income eligibility and allowing access for immigrants and individuals with criminal histories.

“The biggest risk factor for women is financial instability.”

“As a single woman, it’s particularly hard to earn a living wage. Especially if you are experiencing violence. I could go to a shelter, and they would provide me with 6 weeks of help, but what do I do then—because I don’t earn a living wage. I’m just going to have to become homeless again.”

3. Challenge judgment and promote connected, caring communities.

3. Challenge judgment and promote connected, caring communities.

Survivors told us that they were judged for every decision that they made about their relationship. This judgement showed up in all areas of their lives—from friends and family, faith communities, colleagues, law enforcement, health care providers and social service programs, including domestic violence programs. Survivors told us that the climate of judgment made them feel like they had failed and made it very difficult to reach out for support.

Survivors identified the damage of judgement in relation to their histories of abuse, but also, more broadly in terms of their identities and experiences. They told us that they felt judged for their experiences of poverty, issues related to health, mental health and addictions, their abilities, ethnic identities, who they loved, histories of incarceration, how they parented, their gender, or gender identity. Survivors encourage us to address the judgment that separates us, and to work for connected, inclusive communities that promote mutual accountability and support.

“I just feel like there needs to be so much more education about it and there's a lot of blame that people still put on the victim. Well, if you didn't like it, you should have left or you're stupid for going back, which only makes you feel more like crap and then you are definitely not gonna get away. So, I felt like I didn't really get any support from my family or my friends, really. Because they couldn't understand. They couldn't reason it out. They couldn't rationalize my decisions. They couldn't. They just didn't understand.”

4. Make it easy for survivors to access services.

Survivors told us that accessing domestic violence services was difficult. Many were unaware of the services that were available in their community or didn’t feel confident that those programs could meet their needs. They encouraged us to broadly spread information about domestic violence programs, and to build inclusive services to welcome survivors diverse in identities and life experiences. Critically, they told us that a compassionate point of contact made all of the difference in how they felt about themselves, their ability to take next steps, and whether they could trust the programs that are there to support them.

“I feel like there’s no support for people with disabilities… People need to be more receptive of situations where disability comes into play with access to buildings… also removing barriers for using the bathroom including signage that shows respect for those who are trans.”

5. Explore accountability alternatives.

Only about one quarter of the survivors that we spoke with thought that accountability for offenders through the criminal justice system was a helpful solution. These survivors expressed concern that incarceration was a temporary solution that didn’t help them to feel safer, and also that incarceration couldn’t address the root causes of violent behavior. These survivors encouraged us to explore alternatives that could increase community safety, encourage offenders to take responsibility for their actions, and to change.

“We have some excellent programs to help victims and survivors, but we do not have programs to help the abusers. We’ll just land, oh, we don't wanna help them. We’re just gonna put them in jail. Well, I'm sorry, the jail system is not set up to help people. It really makes them more angry. So, that's what I think.”

What we are doing now:

Though we’ve invested over 1000 hours in this multi-year effort, we recognize that listening was just the beginning. We know that what happens next will determine the value of this project. Changing ourselves and the systems that we work with will challenge our ingenuity and resolve.

Since releasing the Re-Centering report in May of 2019, ICADV has worked at the state level and also with member programs to implement survivors’ recommendations. Highlights of action undertaken at the state and community levels include:

Community support—ICADV has focused on the promotion of stable basics through the Coalition’s public policy agenda, investment, and program development. During the 2020 legislative session, ICADV’s advocacy focused on expansions of social safety net programs, support for protections for workers like paid family leave and pregnancy accommodations, and opposition to predatory lending practices. Additionally, ICADV successfully advocated for an expansion in federal housing funds for domestic violence survivors in Indiana and created a housing program at the Coalition to support local communities in accessing the funds. Advocating for economic opportunity and stable basics feels particularly productive because in addition to helping survivors to rebuild their lives, evidence from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicates that these investments can help to prevent violence from happening in the first place.

Community support—ICADV has focused on the promotion of stable basics through the Coalition’s public policy agenda, investment, and program development. During the 2020 legislative session, ICADV’s advocacy focused on expansions of social safety net programs, support for protections for workers like paid family leave and pregnancy accommodations, and opposition to predatory lending practices. Additionally, ICADV successfully advocated for an expansion in federal housing funds for domestic violence survivors in Indiana and created a housing program at the Coalition to support local communities in accessing the funds. Advocating for economic opportunity and stable basics feels particularly productive because in addition to helping survivors to rebuild their lives, evidence from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicates that these investments can help to prevent violence from happening in the first place.- Domestic violence program services— ICADV and member programs are collaborating on multiple strategies to ensure that community services are accessible, inclusive, compassionate and centered in survivor-defined needs.

- Training—The Coalition has engaged members in multiple trainings and organizational audits to increase access to competent services for communities that have been unserved or underserved including communities of color, immigrants and people with disabilities.

- Systems and service delivery strategies—Member programs have begun to engage in regional meetings to identify opportunities to deepen their collaborations to increase innovation and the sustainability of services. Programs are working to better meet survivors’ need for physical safety and stable basics by increasing mobile advocacy, rapid rehousing supports, and flex funding.

- Addressing judgment—In December 2019, ICADV conducted a survey among domestic violence advocates from across Indiana in order to identify the roots of judgment in our field, and the types of support that advocates need in order to do their best work. Survey findings have been used to form recommendations for changes to workplace cultures, employee wages and benefits, training and supports.

- Accountability alternatives—ICADV has convened a cohort of member programs including victim service providers and batterers intervention programs to assess alternative accountability strategies, like restorative and transformative justice practices, that are being used in communities around the country to respond to domestic and sexual violence. The cohort is working with the goal of creating a range of accountability options to enable survivors to choose the option that best supports their safety and wellbeing.

Going Forward

With the conclusion of this first phase of our work, we feel encouraged by the action steps that have already been initiated at state and local levels, and hopeful about the next steps we will take in collaboration with survivors, domestic violence programs and community partners. As we go forward, we maintain our commitment to work in accountable relationship with survivors, and to be guided by the needs of those who have been the most marginalized.

SAVE THE DATE!

Mark your calendar and plan to join our webinar discussion, offering an opportunity to dig deeper into this process:

ReCentering: Indiana's Movement to Ground Domestic Violence Programs in Survivor-Defined Success

Thursday, October 8th at 3pm Eastern/12pm Pacific

Registration information to follow!