By Johnanna Ganz, Ph.D., J. Ganz Consulting, LLC

I didn’t have the words at the time which made it harder to process or understand why it hurt so much and for such a long time. In my first job as a domestic violence victim’s advocate, I found myself hurting and being hurt as I tried to be an excellent advocate with a client who was saying explicitly harmful things about a systemically oppressed and targeted group I’m part of.

“Who you are outside of work isn’t relevant when providing services. This survivor says you’re her favorite advocate which tells me you can still do good work with her. It’s your responsibility to manage your feelings about clients.”

My supervisor shared some (very close) version of the statement above when I asked her how I could respond to the client and correct these myths and assumptions without hurting the relationship. After this conversation with my supervisor, I didn’t even try to get the client to stop saying awful things about me and my loved ones. I continued to work with this client as her primary advocate until she moved out of shelter services—the whole time experiencing active harm and trying to manage my feelings as I was told. This is one of many examples of moral injury on the job as an anti-violence movement worker.

In this piece, I am going to take a brief look at moral injury and how it impacts sustainability as well as how you can choose to manage it.

A brief introduction to moral injury

“Moral injury is the damage done to one’s conscience or moral compass when that person perpetrates, witnesses, or fails to prevent acts that transgress one’s own moral beliefs, values, or ethical codes of conduct.” (The Moral Injury Project)

Moral injury first became better understood when clinical providers were trying to understand and work with war veterans who had witnessed, participated in, or failed to prevent morally distressing events during their employment as a military member. While the term first helped veterans understand what had happened to them, there have been studies on moral injury in other areas such as nursing and medical and first responder. The term has been slowly being applied to many other fields within human services, included domestic violence response.

At its core, moral injury is about having to manage the negative mental, social, and emotional outcomes of consistently having to be involved in or required to be part of decisions, actions, and procedures that violate your most important moral and ethical beliefs. Examples of common moral injuries I see in DV response services:

- Being in a meeting where something deeply wrong or immoral happens, but you didn’t say or do anything to stop it

- Knowing the ethical choice that you should make, but funding sources or agency policies restrict the ethical options for response and require you to make harmful decisions

- Being asked to carry out toxic or harmful program designs that will negatively impact the community you are trying to support

- Having to turn away clients from services or exiting a client from shelter services for culturally aligned or culturally appropriate behaviors for that client’s background

- Being asked “play nice” or “give respect” or “let things go” when confronted with professions or systems that hurt survivors to avoid “upsetting” your community partners

What’s “moral distress” or “moral suffering,” and how are they different from moral injury?

Moral injury, moral distress, or moral suffering? If you’ve been looking into this topic, you will likely see several terms used, sometimes interchangeably and sometimes uniquely based on specific professional field. While the terms try describing the unique elements by profession or experience, each term is focused on describing the pain, negative outcomes, and the damage done to an individual’s sense of self or to a group by being involved in employment decisions or practices that go against what they believe is fundamentally right.

Some folx encourage us to think about moral distress as leading to moral injury. While others suggest that distress and suffering should be under an umbrella label of moral suffering. There is no “right way” to talk about your experiences and more people are more familiar with moral injury. So, to keep the words consistent, I will use moral injury for the rest of this piece.

All these conditions are marked by intense experiences of pain, guilt, shame, betrayal, and anger that are targeted at the self or others. Thinking things like, “How could I do that?” or “What kind of person would let that happen and say nothing?” are common.

How does moral injury impact career sustainability?

Moral injury creates conditions for clinical burnout for workers, but burnout and compassion fatigue are not tied to moral injury. Moral injury is a unique form of occupational stress.

Moral injury hurts workers, hurts services to clients, and hurts the environment and function of agencies. So, when I say that moral injury hurts all of us, I mean it. You, your agency, and the clients you serve all experience worse outcomes and damage when moral injury is left unaddressed.

Here, I am going to focus on the individual outcomes. The short version of the research tells us clearly: your career and personal life will be negatively impacted by compounding moral injuries. The more you experience, the harder it gets to heal. Workers experience increases in negative mental health outcomes (trauma, PTSD, depression, anxiety, etc.), and moral injury shortens the careers of good workers when they do not receive the care and support they need to process moral injuries.

The impacts of moral injuries don’t stay at work when you leave for the day. For many people, they feel like bad people, less like themselves, or they experience moral disorientation. Moral disorientation is when you (1) begin to doubt your own or other’s goodness or ability to do good, (2) feel like you don’t know what is right or wrong anymore, or (3) that you no longer understand or have a moral guide or code that includes you. Moral disorientation is associated with many negative mental and social health outcomes.

How can we repair moral injury when it happens?

We need individual and collective support and many opportunities for repair to heal from moral injury at work. Some of the most common individual treatments for healing from moral injury include:

- Individual clinical mental health therapy with emphasis on responding to traumatic events

- This may include medications and/or additional alternative therapies

- Spiritual support services (religious or non-religious)

- Clinical or community support groups to build connections and openly discuss issues

- Profession change (a.k.a, quit your job and find another field to work in)

- Practicing forgiveness for self and others through cognitive flexibility development

- Lifestyle changes that increase holistic wellbeing (physical, emotional, social, etc.)

Ideas for domestic and sexual violence organizations to foster collective repair for moral injury include:

- Review organizational design and identify/implement changes in organizational or service delivery designs that will decrease moral injury

- Clearly define your organizational values and principles and identify what supports, funders, or partnerships you are willing to lose to stand in your values and prevent moral injury to workers or the agency

- Shift funding strategies to focus on individual donor and community-funded giving to get away from restricted grants or funds that place constraints on agency’s autonomy to decide how to function, language to use, or how to spend funds

- Engage in agency-wide discussions about the topic with supportive resources

- Create group or departmental systems for naming when a decision or action has potential for morally injurious outcomes with resolution process

- Implement strong conflict and feedback processes within the agency that explicitly invites repair for moral injury or conflict

At the core, what most strategies for repair tell us is that we need to heal in the context of community and connections with others. We cannot repair or prevent moral injury in isolation. We need other people to be part of the journey.

“Rarely, if ever, are any of us healed in isolation. Healing is an act of communion.” – bell hooks

Last, we can also get support by identifying our professional values and selecting actions that aligns our behaviors with our values. When we know what our values are and how we align our actions to them, every day, we can build stronger, clearer ethical frameworks that guide us. We also can identify what are moral dealbreakers and where we can be flexible to accommodate diverse viewpoints or ethical frameworks.

Wrap up and questions to support guiding your moral wellbeing

Moral injury is not a normal workplace hazard. Over the next few years, due to cuts to social services and programs as well as changes in policy and procedures and the uncertainty of this moment in US history, the anti-violence field is going to experience increasing moral injury. Those with structurally targeted and oppressed characteristics are more likely to experience the greatest impacts of moral injury because of the structural violence that occurs.

It’s on all of us to respond to and prevent moral injury in our work. We are a community, and we need all of us to be part of the solutions. To help guide your moral wellbeing, please use these questions to start or enhance your journey. And please reach out to J. Ganz Consulting, LLC if you ever need more support or training.

- What parts of my ethical compass can I accept not being in alignment with my working life?

- What parts of my ethical compassion are unacceptable to flex because it would be too damaging to me?

- What parts of me or my wellbeing shouldn’t change because of my work?

- Social, behavioral, emotional, financial, etc.

- How do I want to feel after each working day? To what degree can I do that here?

- Where can I make the most positive impacts in my employment? Does it need to be in this agency/field?

For more information:

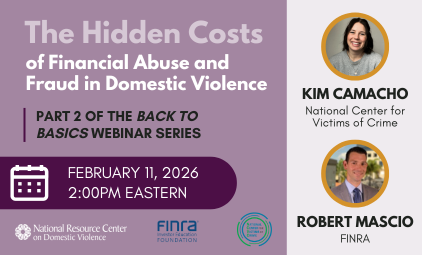

Have you ever had to carry out an action that felt fundamentally wrong in your work? Have you had to make a hard decision that went against your core values or beliefs? Have you witnessed deep harm happen that made you feel guilt or shame, and yet you were powerless to respond? You have likely experienced a moral injury at work. In the webinar, When the Work Hurts: Managing the Impacts of Moral Injury and Career Sustainability in Mission-Driven Work, Dr. Johnanna Ganz takes a deep dive into the key concepts of moral distress and moral injury, with a focus on what it is and how it can show up in mission-driven environments. The presenter looks at how moral distress and injury impact career sustainability and discusses strategies on how to navigate the hard, the ugly, and the painful as well as naming your personal signs that it is time to leave the work.