By Edric Figueroa and Amarinthia Torres

Historically, domestic violence programs were born from the women’s liberation movement of the 1970’s to address the needs of female survivors. Overtime, it has come to be understood that anyone can be a victim of domestic violence regardless of race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, or gender identity. Both research and practice-based evidence underscore the need to improve services for male victims of domestic violence (Stiles, Ortiz & Keene, 2017).

“The men had their own complicated stories of abuse.” - Julia Perrilla

Identifying why male survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) do not reach out for support has become a popular research topic across the field. Studies have found that men fear that their masculinity would be perceived as diminished if they access survivor services. This research also states that many men feel that traditional domestic violence (DV) services were not set up for their needs. However, these help-seeking barriers are not unique to male survivors.

Women survivors from diverse racial and cultural backgrounds also report more hesitation to utilize traditional DV programs. Further, LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer) survivors experience significant barriers to seeking support from DV. We raise these facts not to diminish the real impacts of IPV on male survivors, but to critically examine the recent focus on serving men. This focus raises the question, “Are we bringing our interventions to scale for the survivors most impacted by IPV?” If the COVID-19 pandemic has taught the US anything over the past year, it is that health equity advances for everyone when the country centers care on those most marginalized. If this public health approach is applied to IPV and the needs of survivors most impacted by violence (LGBTQ folks, Black and survivors of color) are centered, this will inevitably lead to serving males and survivors of all genders with increased autonomy and dignity.

Serving Survivors at the Margins

Oppression is ever-present and lethal. The recent killing of Black Americans, mass shootings targeting Asian and Latinx communities, and the ongoing violence against trans and queer communities are stark reminders of this fact. Serving survivors at the margins means naming who is at the periphery of the larger, dominant groups in society. Who is receiving marginal attention compared to the majority? Who’s at the edge and who has more distance from the edge? Understanding the differing rates of violence across groups is critical in serving those most impacted by IPV.

Women experience higher rates of IPV than men with women of color experiencing the highest rates of IPV of any reported population. When looking at victimization based on sexual orientation, the same survey found that bisexual women experienced a significantly higher lifetime prevalence of rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner when compared to lesbian and heterosexual women. Like much of IPV research, this data did not ask about gender identity. However other studies have estimated that upwards of 50% of transgender individuals have experienced IPV. LGBTQ survivors experience the highest rates of hate-motivated violence in this country. They also have the lowest rates of advocacy support, made worse by the barriers of gender-segregated services in the anti-violence field (shelter, support groups, batterers-intervention-programs, etc.). Black girls, women and non-binary survivors are hyper vulnerable to abuse, less likely to be believed, and are disproportionately met with severe punishment when they defend themselves. Given this, groups most impacted by IPV are women of color (particularly Black and Indigenous women) and LGBTQ people (particularly bisexual, trans and BIPOC people). Groups less impacted by IPV are white, cisgender, heterosexual men.

Domestic violence programs play a key role in shifting from a culture that tolerates difference to one that embraces intersectionality. Eight years ago, the first federal protections against LGBTQ discrimination were introduced through the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act. Included was the call to serve survivors of all genders. We have seen programs struggle with this shift. This moment is an opportunity for the anti-violence movement to center the dignity of all survivors by getting real about how gender operates in a white, hetero-patriarchal nation. This oppression is operationalized within DV programs and manifested interpersonally even when men are not present.

To serve survivors of all genders, advocates must have a deep understanding of patriarchy, power, and coercive control. So while we develop resources on how to decrease disparities for diverse survivors (including gay men, bi+ men, and trans men), the movement can no longer dance around the real topic that makes serving DV survivors of all genders difficult: patriarchy and power.

How does Patriarchy affect Survivors of all Genders?

So what do we mean by the term “patriarchy” and why is it relevant to a conversation about supporting survivors of all genders? We characterize patriarchy as a system of beliefs, practices and policies, both at an individual and institutional level, which establishes a binary of two distinct genders, man and woman. Within this binary, cisgender men are given power and privilege at the expense of basically everyone else, including women, transgender people, intersex people, and gender non-conforming people. Similar to other forms of oppression, patriarchy is intertwined with other types of social inequality and exploitation such as white supremacy, ableism, sexism, classism, and heterosexism to name a few.

So what do we mean by the term “patriarchy” and why is it relevant to a conversation about supporting survivors of all genders? We characterize patriarchy as a system of beliefs, practices and policies, both at an individual and institutional level, which establishes a binary of two distinct genders, man and woman. Within this binary, cisgender men are given power and privilege at the expense of basically everyone else, including women, transgender people, intersex people, and gender non-conforming people. Similar to other forms of oppression, patriarchy is intertwined with other types of social inequality and exploitation such as white supremacy, ableism, sexism, classism, and heterosexism to name a few.

Patriarchal beliefs, practices, and policies are everywhere and affect everyone. Folks of all genders are capable of enforcing and maintaining patriarchal beliefs; however, only individuals or groups with access to institutional and cultural power are able to back up those oppressive values and beliefs through inequitable policies and laws. Individual people of color may hold prejudice towards white people and individual women may hold prejudice towards men, but neither people of color nor women have enough access to institutional power to manifest those prejudices into large scale disparities or unequal distribution of resources to white people and men.

Patriarchy reinforces and maintains the hierarchy of gender and power. Maintaining the hierarchy of gender and power is at the root of gender-based violence. The tactics used by abusive partners rely on patriarchal policies that are also embedded in the systems survivors are reaching out to for support. To truly support survivors of all genders, we believe the anti-violence field needs a robust analysis of gender and power deeply informed by patriarchy.

“The soul of feminist politics is the commitment to ending patriarchal domination of women and men, girls and boys. Love cannot exist in any relationship that is based on domination and coercion. Males cannot love themselves in patriarchal culture if their very self-definition relies on submission to patriarchal rules.” - bell hooks

Examples of how we’ve seen patriarchy impact survivors of all genders:

- Enforcing rigid gender roles and unreasonable expectations related to gender that limit one’s choices and sense of self over time;

- Using regressive and harmful notions of gender to police gender expression;

- Internalized toxic masculinity;

- Femmephobia and misogyny;

- Sexist stereotypes about who gets to be angry, emotional, or take up space in the relationship;

- The belief that the system works or is biased in favor of women: “if I was a straight woman, I would be able to get this domestic violence protection order enforced right away.”

Without a robust analysis of gender and power informed by patriarchy:

- We ignore that power is gendered;

- We disregard the clear data on groups disproportionately impacted by IPV and therefore efforts to support them are lessened;

- Power and who is wielding it (at individual and institutional level) is obscured;

- We under explore the complex interplay between gender and surviving coercive control in our advocacy;

- We struggle to support survivors in their efforts towards liberation from gender oppression;

- We minimize or ignore the impact of internalized sexism (sexism, a weapon of homophobia);

- The anti-violence field loses credibility as a social movement by not connecting IPV to larger systems of oppression.

Key Recommendation: Create gender-conscious, not gender-neutral services

A gender-neutral service model might welcome survivors of all genders but through a lens of “we don’t see gender” and “we treat everyone the same.” While this may sound like the simplest solution to increase gender-access, this model ignores the impacts of power and patriarchy. If we “don’t see gender” we also don’t see the disparities caused by gender oppression.

This model has led some agencies to simply create new, but separate programs and policies for male-identified survivors. Dividing up services out of concern for the gender dynamics that may arise can increase isolation for survivors. For example, providing hotel stays instead of confidential shelter or only offering one-on-one advocacy to male-identified survivors instead of support group. The separate-but-equal service delivery that often comes with a gender-neutral model reinforces the very notions of patriarchy that create interpersonal violence in the first place.

Gender-conscious service models aim to mitigate the impacts of oppression on survivors’ lives across the gender spectrum. As we explored above, women, femmes, Black, LGBTQ, and other people of color bear the disproportionate impacts of all violence. Our advocacy services cannot be neutral and must address patriarchy in necessary and meaningful ways.

Gender-conscious models reflect on whose safety or comfort is prioritized before making the decision to segregate support services. For example, we know that people-of-color spaces can be transformative to a survivor’s well-being. If programs decide to segregate their services, it must be to increase solidarity between survivors and not to avoid difficult or uncomfortable growth opportunities for staff and survivors alike. Additionally, remember that self-determination is a hallmark of advocacy. With enough trust, advocates can help survivors decide on how/if they want to challenge or expand upon their notions of a safe space by joining a mixed-gender group or inclusive program.

Gender conscious services can start with:

- Organizational values statements explicitly naming patriarchy as a barrier to ending violence and committing to work against this and other oppressions;

- On-going training on how to work with diverse survivors (LGBTQ individuals, Black and POC, etc.) through an intersectional lens;

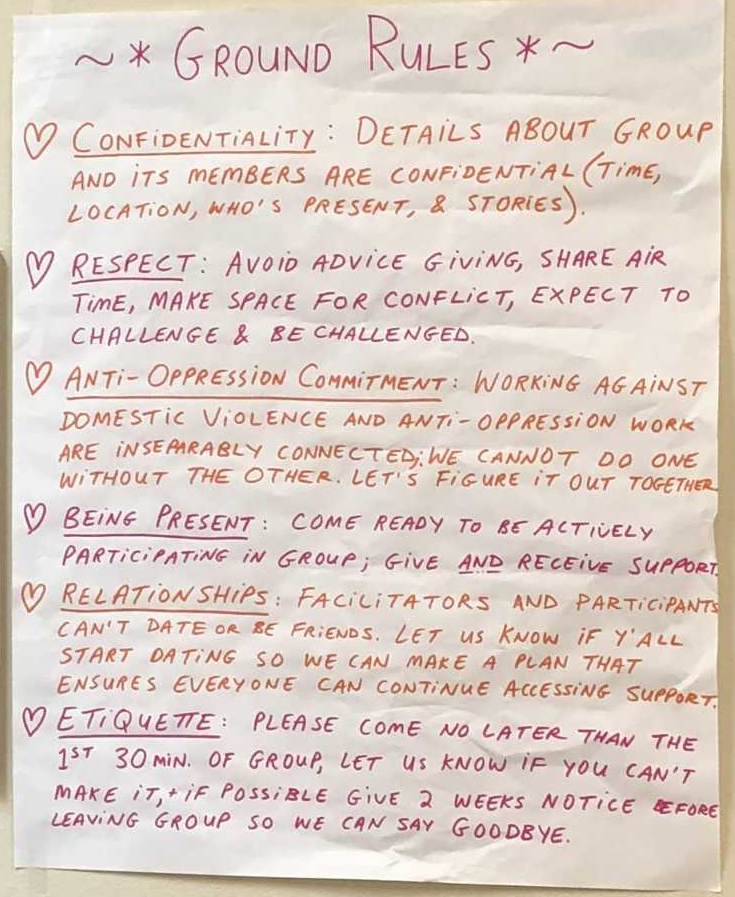

Creating group agreements that state people of all genders and orientations are welcome here and that discrimination is not;

Creating group agreements that state people of all genders and orientations are welcome here and that discrimination is not;- Correcting incorrect, biased, or harmful comments rooted in oppression when necessary;

- Advocacy that explores the real-life impacts of systemic oppression with survivors;

- Normalizing check-ins about power dynamics for staff and survivors;

- Creating clear expectations of what your support is for;

- Asking for transparency if outside romantic relationships between survivors in the same program(s) emerge;

- Utilize team advocacy models;

- Asserting our expertise about what constitutes coercive control.

For those interested in having gender-inclusive services for survivors of all genders, you’re in luck—you already have many of the skills! The same skills that strengthen support groups, one-on-one survivor advocacy, and prevention activities also support your ability to work with IPV survivors of all genders!

We all benefit from programs affirming that people of all genders need support to survive the impacts of abuse. By getting real about patriarchy and power, we are better equipped to support survivors of all genders who are most impacted by its harms.

Finally, what if the field did not hesitate to exert its expertise about what constitutes IPV? We will explore why ensuring survivor-specific support is critical to serving survivors of all genders in Part 2 of this TAQ. Part 2 will be available on VAWnet in June 2021.

Additional Resources

Serving Male-Identified Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: This paper offers guideposts for responding to the needs of male-identified victims of intimate partner violence. It is meant to be a resource to foster meaningful dialogue around supporting inclusive services for all victims and survivors seeking safety and healing.

NRCDV Radio Episode 9: Responding to the Needs of Male-identified Survivors of IPV: This special edition of NRCDV Radio's Stories of Transformation features Eric Stiles an advocate with specialized expertise in child sexual abuse intervention and anti-sexual violence work in rural areas, as he discusses male victims and offers guideposts to providing survivor-centered services.

WEBINAR: Enhancing Services to Male Survivors Series: Changing the Narrative: In part one of the Enhancing Services to Male Survivors Series, presenters engage in a discussion about including a gender-conscious philosophical framework for enhanced services to male survivors of domestic violence that links to and builds upon the historical roots of the movement against gender-based violence and is consistent with anti-discrimination laws and related grant conditions.

WEBINAR: Enhancing Services to Male Survivors Part II: Voices from the Field: Part II of the Enhancing Services to Male Survivors webinar series showcases the work of two domestic violence programs that are leading the way as they expand their services to male survivors. The presenters share lessons learned through this process and offer promising practices to help build capacity to recognize and respond to the needs of male-identified survivors of domestic violence.