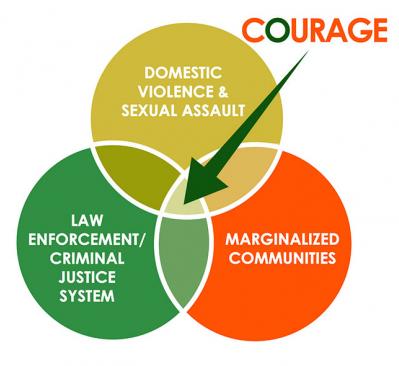

This special collection is a product of the COURAGE in Policing Project, jointly supported by the Human Rights Clinic at the University of Miami School of Law, Casa de Esperanza National Latin@ Network, and UN Women. [Note: Rosie Hidalgo contributed to the production of this Special Collection prior to January 2021, in her capacity as Senior Director of Public Policy, Casa de Esperanza (now Esperanza United).] The purpose of this special collection is to compile resources focused on improving the law enforcement responses to domestic violence and sexual assault.

Domestic violence, sexual assault, and other forms of gender-based violence (GBV) are pandemics that are globally ubiquitous, despite decades of efforts to address these ills through public health, criminal justice, education, and social welfare sectors. Despite the devastating prevalence of GBV, the United Nations (UN) has reported that in most countries, less than 40% of women who experienced violence sought any sort of help, and of those, less than 10% sought help from the police (United Nations Statistics Division 2015). This reflects a profound mistrust of state systems whose frontline responders are usually law enforcement officers and whose purported mission is to protect and serve.

We hope that this special collection will provide various perspectives and resources for advocates, law enforcement leaders, and others who are considering ways to improve law enforcement responses to gender-based violence, particularly in underserved or marginalized communities. Our hope is to expand and improve pathways to safety for survivors.

We recognize that there are many unanswered questions that may come up for readers in the review of this special collection. These may include questions such as: how have advocates approached law enforcement issues? What is the historical impact of the work done by advocates? What is the ability of law enforcement to implement measurable and sustainable change? and how can law enforcement evaluate and correct itself at this point? While this special collection does not directly answer these questions, we recognize the importance of exploring these pertinent questions in future collections to better identify and prevent gender bias in the law enforcement response to sexual assault and domestic violence. We also acknowledge the need for rigorous evaluations of existing law enforcement training programs to bring greater accountability, enhance credibility, and bridge gaps in the program to ensure training effectiveness.

In the future, the COURAGE project plans to develop a collection of resources highlighting the importance of different pathways to safety, particularly for survivors who want alternatives to the criminal legal system, such as “violence interruption” programs, restorative and transformative justice, collective healing, economic justice, and health and housing justice. We welcome your feedback and ideas.

We approach this work with the intention of dismantling misogynist, anti-black and racist norms that are prevalent throughout U.S. society, including in the criminal legal system. Indeed, it is well understood that many survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault choose not to engage with the criminal legal system for a variety of reasons, including: a history of violence by law enforcement and other state agents against women, black and minority communities; fear of the immigration, child welfare, public assistance, and other consequences for survivors and their family members; deportation, exploitation, and a desire to protect one’s family from justice system involvement. Nonetheless, for the victims who do interact with the criminal legal system, the focus of this initiative is to make existing law enforcement systems more trauma-informed, survivor-centered, and accountable.

While criminalization of individuals who inflict GBV has historically been viewed as a proxy for justice, advocates and scholars are proposing alternative frameworks, such as “violence interruption,” restorative justice, community justice, collective healing, economic justice, health and housing justice, and “police abolition.” We endorse these calls for increased research and investment in non-criminal approaches to preventing and responding to GBV, and we believe they are in line with a human rights-based, “due diligence” approach.

While we must develop and embrace a long-term vision for safety, justice, and healing for survivors, we also believe that we must develop viable models to improve police response to GBV for the foreseeable future. For such a devastating and deadly problem, we must approach the problem in the here-and-now with tactical precision. This means investing in the alternative approaches outlined above, while insisting on improvements to the criminal legal system that currently exists.

While the role of law enforcement will likely evolve in response to these crises, it remains an important system actor in the GBV context for the foreseeable future. It is thus critical that LEAs espouse and implement the following principles, expanding on the DOJ Guidance: accountability for officer-perpetrated GBV; trauma-informed interactions with survivors; effective investigation of GBV reports; and attention to intersecting forms of discrimination. Doing so will help prevent gender and other intersectional forms of bias, thereby improving responses to GBV and contributing to a safer world for all of us.

The authors are grateful to colleagues from UN Women who contributed feedback and ideas to this special collection: Mirko Fernandez, Laura Capobianco, and Caroline Meenagh.